Glass ionomer cement, or GIC, as it’s often abbreviated to, is a dental restorative material that can be used as a filling material, sealant, liner or luting cement. On the rise in popularity due to the growing demand for teeth colored restorations, glass ionomers provide unique advantages over alternative restoratives, most notably the ability to release fluoride. But like all restorative materials, it’s important to look at the pros and cons of the material’s composition, uses, physical and mechanical properties.

Glass Ionomer Ingredients

In general, glass ionomer cements are classified into three main categories: conventional, metal-reinforced, and resin-modified. These variations mean glass ionomer cement can have a range of compositions, but the chief ingredients of conventional glass ionomer are basic glass and an acidic water-soluble powder that sets by an acid–base reaction between the two components. It is this composition which gives glass ionomer its unique ability to release fluoride, a mineral that can reduce cavities and tooth decay, and physically and chemically bond to tooth structure with no need to etch or prime.

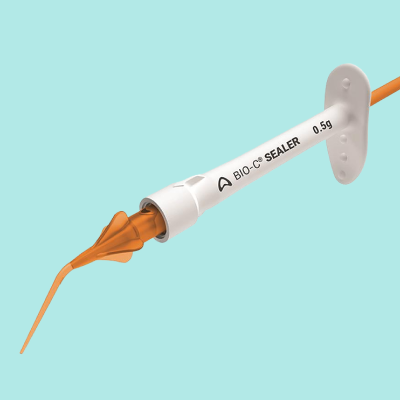

Glass ionomer cement can be supplied as powder and liquid (which are hand mixed on a glass slab using a spatula), pre-dosed capsules (for mixing in an amalgamator), or ready-to-use capsules (dispensed directly into the cavity using an injector gun). One of the more recent glass ionomer advances is a resin-modified GIC that combines traditional GIC ingredients with the addition of light-curing resin to increase strength and wear resistance, thus bringing together the advantages of composite resins and glass ionomers. Before resin-modified glass ionomer was introduced, metal-reinforced GIC featuring a silver-amalgam alloy power was the hybrid of choice, as it increased the strength of the cement and provided radiopacity.

Advantages

- Requires minimal removal of healthy tooth structure

- Decent match to tooth colour, especially in the case of resin-modified glass ionomer cements

- Ease of placement

- Versatility of use

- Bonds exceptionally well to tooth surface without the need for a bonding agent

- Hardens immediately by light curing

- Releases fluoride over time

Disadvantages

- Relatively low durability – more prone to fracture and wear than composites

- Lower tensile strength than composites

- Limited shade ranges in comparison to composites